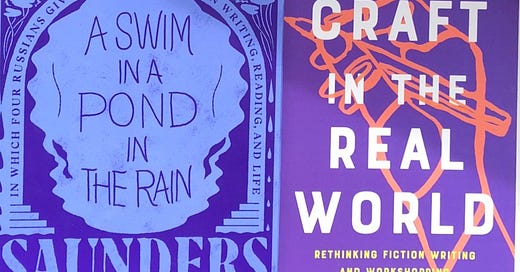

I’ve been working on this newsletter for half a year now and have noticed myself reading towards an audience (you). I’ve started putting together little “reading programmes” for myself in anticipation of writing about books together. I saved these two books for a double feature since they’re both about the art and craft of writing.

I used to believe that writing was an innate talent and that it couldn’t be taught until my friend Yu-Mei, who teaches writing herself, disabused me of that notion. Writing, like all other art forms, is a skill to be honed. Pure talent might manifest in an intuitive understanding of how to tell an engaging story but learning how to wield the elements of a story – structure, syntax, characterisation – can be worked on.

The two books present very different views on fiction writing. Salesses is writing against the hegemony of MFA Writing and advocating for a more expansive view of good fiction. Saunders’ book is literally a version of his short story class in the MFA programme at Syracuse University. Reading them in tandem clarified my own views on what makes good fiction. Ultimately, both books are written by authors who love writing and want to cultivate the best literary community/ies possible.

This is what George Saunders has to say about reading in his introduction:

To study the way we read is to study the way the mind works: the way it evaluates a statement for truth, the way it behaves in relation to another mind (i.e., the writer’s) across space and time.

[T]he part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.

Isn’t that beautiful!

Craft In The Real World by Matthew Salesses

This book is split into two sections: the first is examination of craft and the cultural expectation of what good fiction looks like, the second is on the writing workshop as a pedagogical tool. As a reader, the first section was more relevant to me. I imagine that anyone who teaches/attends writing classes would have a lot to learn from the second section.

If you read contemporary fiction, the first half of Craft helps to contextualise a lot of the aesthetic choices that you’ve come across. Salesses’ argument is that MFA programmes enforce a particular view of good fiction. The workshop format usually requires writers to submit a piece of work and surrender it to their classmates for critique. The writer sits silently while they hear their peers’ responses. Salesses makes the point that this leaves the writer’s work up to the forces of the majority; this often disadvantages minority writers. He gives this example – fiction writers are often encouraged to choose “striking” sensory details and to defamiliarise the familiar. But what is familiar to one person is often unfamiliar to someone from a different cultural background. A story set in Korea might include a detail like “the man’s incorrectly buttoned coat” which might be striking to the writer. But a white American audience might suggest that the writer include “an extreme example” like “passengers eating kimchi in their box lunches”. According to Salesses, craft is a set of cultural expectations that is shaped by the audience and their experience of the world. It is impossible to write to a generic audience and the best way to nurture writers of diverse backgrounds and experiences (and to make space for a more vibrant literary scene) is to expand our notions of what craft can be.

In other words, an orientation toward the world does not originate in an individual, but in the world. What we consider unjust is shaped by shared values. If our culture says we should be able to own land, then it feels unjust when a stranger builds his house in our yard. If our culture says no one owns the land, then it does not feel unjust when a stranger builds his house in our yard. We have no yard.

The above illustration has massive implications on plot, especially on what is considered sufficient conflict. The dominant story arc for a lot of contemporary fiction (not just books but movies too) is a beginning where conflict is introduced, a middle where conflict is faced, and an ending where conflict is resolved. This is hardly the only way to tell stories. Asian storytelling traditions sometimes follow a four-part structure (introduction, development, twist, reconciliation) where conflict is not necessary. It’s easy to imagine that a writer from a culture other than the dominant Anglo-American one could write a story about a family moving into his “yard” without it being a story of conflict or land ownership. It shouldn’t automatically be judged as poor storytelling because it does not conform to a majority view (in Western fiction) of good writing.

This is hardly the only gem from Salesses’ book, I just can’t fit all of it into this newsletter. I’m glad I bought it, I imagine I will be referring to it often. I really recommend it.

A Swim In A Pond In The Rain by George Saunders

George Saunders is a fantastic short story writer and a teacher at the Syracuse University MFA Programme. This book distills the lessons he’s learned and taught from years of running a course on Russian short stories. I really enjoyed the structure of this. There are seven “iconic short stories” from classic Russian authors. Each is interspersed with commentary from Saunders about what he likes and why each story works.

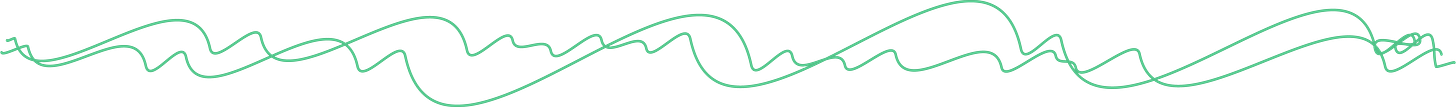

That said, I struggled with some of the story choices.

The stories are polarising. Newsletter reader (and cool person) Deborah Augustin didn’t really get into them either –

– and neither did my dear friend, and the reason I even read George Saunders to begin with, Rowan.

What I do like about the book is the benefit of reading alongside Saunders. His assessment of the stories seem like universal recommendations but, because I found so many of the stories so unlikeable, it was easy for me to observe where my opinions diverged from his. Reading this right after Salesses’ book gave me the critical tools to identify rules that could be broken. Just take a look at this excerpt from Saunders:

We might think of a story as a candy factory. We understand the essence of candymaking is … making that piece of candy right there. As we walk around the factory, we expect everything in the place – every person, every phone, every department, every procedure – to be somehow related to, or “about,” or “contributory to” that moment of candymaking. If we stumble on an office labelled “Centre for the Planning of Steve’s Wedding,” we sense inefficiency.

His view of story elements and plot are instrumental. Everything must be in service of advancing the plot. Saunders includes three stories by Anton Chekhov in this volume, the very same Chekhov who said “remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.” Salesses would probably disagree with this being a universal rule.

It was actually quite nice to learn about the rules of “classic” fiction. I may not agree with their essentiality but I love learning about how things are made.

If you only read one story in this volume, please read Gooseberries by Chekhov. It gives the book its title. It is gentle, it is beautiful. It actually does not have a plot that fits the rising action, climax, falling action model. If anything, it demonstrates how malleable these “rules” of fiction are. But if you don’t want to read Saunders’ assessment, just read the story. It’s worth your time.

More links

If you’d like to learn more about the history of the critique of MFA fiction, you can read this (very cynical) essay from 2010. I first read it 5 years ago in an old issue of n+1. While I don’t agree with the author’s conclusions (nor his negativity), I think he does a great job of illuminating the material concerns (money) that govern how fiction writers have to work. That essay was turned into a book. You can read more about that in this review from The New Yorker.

Here’s an excerpt of my favourite section of Matthew Salesses’ Craft in the Real World.

25 Essential Notes on Craft from Matthew Salesses

8. Since craft is always about expectations, two questions to ask are: Whose expectations? and Who is free to break them?

Some short stories

This George Saunders short story might be my favourite that I’ve read from him. It’s titled Escape from Spiderhead and is apparently going to be made into a Chris Hemsworth feature which I will not be watching. You might not sense this from reading his book because he is very modest but Saunders is a master of the short story form. He’s also a lot funnier than the Russians.

This is a short story from Brandon Taylor, one of the most talented writers I’ve ever read. He’s talked publicly about not writing “for the white gaze”, which speaks to the audience specificity problem that Salesses brings up. He also, annoyingly, writes a fantastic newsletter. I might regret linking to this because I will lose my readership. He’s very very good.

Saunders writes about fiction that “denies consensus reality”. He’s writing in response to a Gogol story where a man’s nose leaves his face and goes for a walk. Despite it not being “realistic”, it is still truthful in its unbalanced narration. I immediately thought of Jack Vening’s writing, which is all just a little weird. Here’s a short story that I like but I think subscribing to his monthly serial fiction newsletter, Small Town Grievances, is more fun. It’s a bit like Welcome to Night Vale but funnier.

A tote bag carrying icon! See you next time!