If you’re reading this before 6 November 2022 and don’t already have plans for your Sunday afternoon, you might enjoy this panel I’m on at the Singapore Writers Festival. I’ll be talking about Tote Bag Library. This edition is more about the Internet than it is about books and I think that’s what my contribution to the panel will be as well.

Briefly: Covid left me tired all the time. Walking, reading, and especially writing, have become much harder than they used to be.

All I’ve consumed recently has been that. Brief. In working my way back to reading at my usual clip, I’ve forced myself through essays and novellas. I recently read a novel written in the speedy format of a Slack chat. Post-Covid fatigue has played a big part in this slowdown. But now that that’s tapering off, there’s been another culprit: TikTok.

What an app! It’s markedly different from when I last used it in 2018. The app no longer shows me teens dancing in messy bedrooms. It’s slick now. Professional. Adults with fully-formed careers venture online to extend the reach of their brands. There are TikTok creators that specialise in telling other TikTok creators what content to produce in order to go viral. They do this work in public and for free in the hopes that they either get headhunted by a communications agency for brands or they get turned into the brand themselves. Even the bedroom dancing teens are millionaires now. There’s still plenty of irreverent content but the possibility of an ordinary user going pro always looms in the background.

The algorithm pushes me content it knows I will watch. Every second longer I linger on Video A instead of Video B informs what I get to watch next. I’ve noticed myself scrolling past videos only seconds after they begin. I have little patience for chaff, yes, but also no openness to being surprised. If it isn’t good immediately, it’s not worth sticking around to find out if it gets better. There’s no way this is good for my attention span.

I decided to work harder. After watching countless TikToks set to a number of Bo Burnham’s songs, I decided to watch his hour-long special Inside to dip my toes into the waters of longer content. I had to split my viewing into several sessions over several days but I’m not that sure that was up to my inability to pay attention.

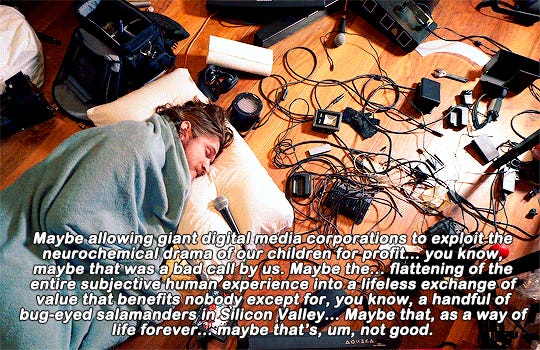

Filmed over the early months of Covid, Inside is a comedy special that isn’t very funny. It wants to make you think more than it wants to make you laugh. Or maybe it does want you to laugh? A common question asked through the special is whether comedy even matters at a time like this.

A few of the musical numbers are entertaining but the audience doesn’t get to stay entertained for long. The film is punctuated with scenes of him talking about how depressed he is. More than anything, Inside is a time capsule for the early days of lockdown. The middle class had an incredibly abstracted relationship with the world outside of ourselves during quarantine. My work, my leisure, my social life all took place over the Internet. I lost a significant chunk of my income because there were no more shifts to work. How long was I inside for? Three months? I can’t remember without looking it up. I can only mark time by its dominant social media trends: dalgona coffee, Tiger King, Chloe Ting’s ab workouts.

I’ve been online for more than half my life. I’ve created selves on Neopets, Friendster, Bebo, LiveJournal, Blogspot, Xanga, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and now Substack. Bo Burnham also grew up online, I remember being impressed by his early YouTube videos. Unlike most of his peers who are still creating today, he’s managed a successful leap off social media. He’s made an A24 film and this special made it to Netflix. That’s why his successful bits in Inside land so well. He knows what it’s like to straddle URL and IRL.

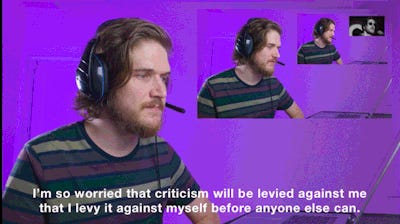

In this bit, he starts a chain of reaction videos. He begins by reacting to one of the songs he’s just performed and goes on to react to each subsequent video in an act of meta-criticism. He’s fluent in the visual and discursive language of the web. The screen layout in this scene is familiar to anybody who’s spent time on YouTube where videos reacting to other videos are a reliable staple for creators who need to constantly churn out content. The self-awareness he employs sounds an awful lot like the therapy-speak that’s come to dominate the way people communicate online. Even the conceit of criticising one’s own criticism is reminiscent of how social media posts are frequently filled with disclaimers in order to ward off bad faith interpretations.

The pandemic forced more social interactions online. While older folk wring their hands at the prospect of Gen Z’s atrophying social skills, there aren’t enough people who are worried about larger swathes of human communication being held at the whims of billionaires. As I write this, I have another tab open to keep an eye on Elon Musk’s erratic decisions about Twitter’s future. It’s increasingly possible that Twitter will cease to be a viable platform for socialising. I will miss it greatly. I’ve learned so much from the experts who use it, discovered work by writers whose publishing houses don’t have huge marketing budgets, and I’ve made friends. I’ve been on the website since 2009, when I was 15 and Tweeting by SMSing my thoughts to a bot during recess. It’s strange to think that a large part of how I’ve socialised over the last decade could disappear because a rich man made a stupid business decision. In the same vein, Burnham sings songs about how the same capitalist forces that corrupted the Internet gave him a career. The romance of being an artist is fictitious. We never solely create what inspires us. We dance like puppets to the feudal lords’ tunes.

Inside is boring and pedantic at times and trite at others. Burnham often makes reference to his position as a straight white man — partly because it’s true and it does determine how he moves through the world but also partly because it is the right thing to say. But I suppose that’s the impotence of being correct. Maybe we just have to contend with the TED Talk-ification of art because the world is so bad, all the time?

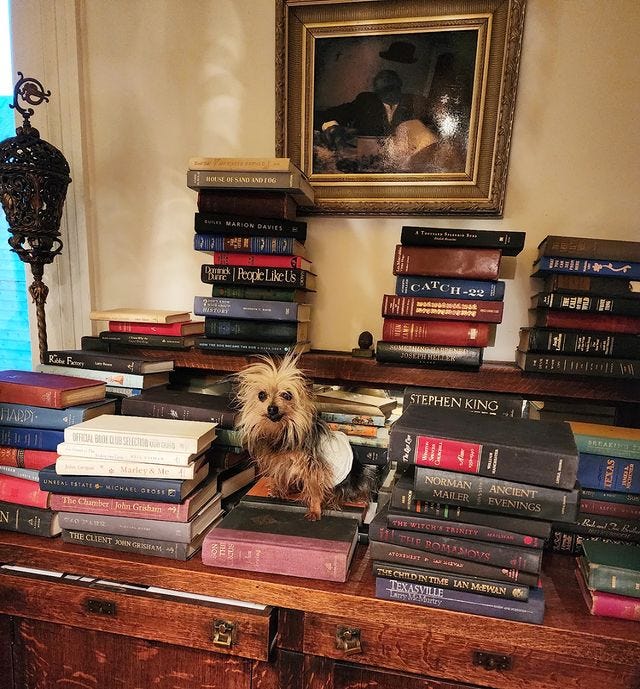

Here are some books I’ve read recently

Two novellas from Fitzcarraldo Editions: Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au and Paradais by Fernanda Melchor (trans. Sophie Hughes).

They’re very different. Au’s book is subtle, the emotional shifts are like shadows on a wall fading as the light changes. It’s about a daughter and ageing mother on a trip to Japan. I’m generally unimpressed by stories where characters travel to Japan and have deep but understated epiphanies however this book is so well-written that I will pretend I don’t mind the setting.

Paradais is written in the same frenzied and vulgar tone that Hurricane Season is. Also like Hurricane Season, it’s a sober picture of inequity and determinism. I strongly recommend it but only if you have the stomach for violence of all sorts.Someone Else Is Typing is a novel told through Slack messages. I didn’t plan it but it was great to read while thinking about how Internet platforms structure our communication. Despite the limits of the medium, it manages to be funny, tender, and intelligent all at once. Sometimes gimmicks work!

I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to update this newsletter! It’s partly because I’ve been working on commissions for other publications + hustling to make the next issue of Mynah possible. I’ll include links to some of my work in the next edition. Thank you for reading!