For two weeks in August, I put all my books away and played Disco Elysium. It wasn’t intentional; I just found the game so immersive that I could think of little else when I was away from it. I described it to a friend as a “game for readers”. With over one million words in the game, there’s a lot to read. Luckily, Disco Elysium is the best thing I’ve read all year.

In Disco Elysium, you play a cop who’s lost his memory after a legendary and destructive bender. The player’s job is reconstruction — you have a murder to solve and you have to figure out who you are. All of this is set in Revachol, a city trying to rebuild itself after a crushed Communist revolution. The game paints a beautiful and tragic picture of a defeated city that’s trying to breathe again. The statue of the old monarch has been defaced with a bullet. There’s a building called the “Doomed Commercial Area” where businesses go to die. You meet drug-addled preteens and disillusioned teenage vandals. You also meet enterprising businessmen, loyal union members, and (my favourite) erudite/pretentious undergraduates who are trying to revive the spirit of Communism.

This game doesn’t have combat or multi-jump levels to clear. It’s a conversation simulator and rewards the type of player who doesn’t skip dialogue to get to the action. (There is no action.) You unlock different dialogue trees by allotting points to various skill sets. These skills are the main gameplay mechanism but they also, seamlessly, make up your character’s personality. I played a character who was heavy on Intellect so I was rewarded with a play run that was full of trivia about Revachol. If I played a more Empathy-forward character, I would have had more luck getting guarded characters to open up to me. The personality you create for yourself dictates your experience of the game. You make more progress the more you build yourself up. I think that’s poetic.

I have a lot to say about the plot, which is as rich as any literary fiction I’ve read recently (the ending, so beautiful), but I’m intentionally withholding details because I really want you to play this game. Go in blind like I did and enjoy Disco Elysium. I’m in a strange bind: I can’t stop thinking about this game but I really want to forget it so I can play it all over again.

Because you’re here for the books

Here are 4 books I’ve read in recent months that I haven’t told you about yet. We’re mostly done with 2021 and I’m still waiting for my book of the year. May it hit me on the head soon.

Great Circle is a novel about the fictional aviator Marian Graves. This is a 600-page epic that spans the circumstances of Marian’s birth all the way to her disappearance during her north-south circumnavigation of the earth. What a feat of writing. The writer Maggie Shipstead not only gives the reader rich and sensitive historical fiction but complements it with a second narrative strand about a present-day Hollywood adaptation of Marian’s story. I’ve seen reviewers suggest that the second storyline was a distraction. I disagree. If anything, watching Hollywood attempt to piece together Marian’s life from fragments and artefacts provides a great meta-commentary on the nature of biography. I finished this book in a weekend. It wasn’t easy but it was rewarding. I would have enjoyed it a lot more if it wasn’t about aviation (I skipped the detailed descriptions of flying equipment) but that is a matter of personal taste. It’s an old-fashioned feminist story: a woman pursues her passion despite the forces of the patriarchy being against her. It’s not entirely my thing but I can see a very large audience for it. Incidentally, Great Circle is on the Booker Longlist. The shortlist will be announced some time next week, I’m curious to see if it makes it.

I’ve previously described Akwaeke Emezi as one of the English language’s best living writers. I still stand by that assessment but this book didn’t do it for me. Dear Senthuran is a memoir told in a series of intimate letters. If you’ve read their first book, Freshwater, the themes in Dear Senthuran will be familiar to you. They write about violence, about rising above violence, and about when it’s not possible to overcome it. They are also concerned with the place of the ọgbanje in the world. An ọgbanje is an Igbo spirit that’s born into a human body. Emezi says they are an ọgbanje and writes from this vantage point — not a bridge but suspended between two impossible footholds. The writing in this book is powerful, especially when Emezi is writing defiantly.

These men are always like that. They want you to desire their approval, their validation, to feed them a bright stream of love and support and the sheer drug that is belief, the engine that is belief, the catalyst that is belief. You’re not supposed to grow up or outgrow them, to reach a place where they have more to learn from you than to teach you. You’re supposed to be sticky with amber, gazing at them as it sets, settling you into a brilliant stillness. They deeply value your mind, but as a resource, as a glittering mind.

A selfish reader could claim some of these words for themselves in a move of Girlbossification. But I don’t think these lessons can be generalised. Why this book didn’t work for me was that I didn’t believe I was meant to read it. The intimacy (many of these letters are addressed to loved ones) is insular and I felt uncomfortable intruding. In Emezi’s belief system, they are an embodied god. There is nothing relatable about that position. Relatability is never a marker for the success of a book but I did wonder what role the reader played here. I felt like I was standing in a corner while two people carried on a conversation in hushed tones. The book is vulnerable but I didn’t think it was generous.

As an affluent, self-selecting group of people move through spaces linked by technology, particular sensibilities spread, and these small pockets of geography grow to resemble one another: the coffee roaster Four Barrel in San Francisco looks like the Australian Toby’s Estate in Brooklyn looks like The Coffee Collective in Copenhagen looks like Bear Pond Espresso in Tokyo. You can get a dry cortado with perfect latte art at any of them, then Instagram it on a marble countertop and further spread the aesthetic to your followers.

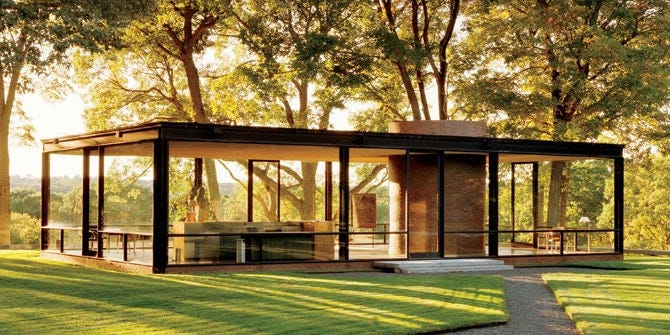

The above passage comes from Welcome to AirSpace, an essay by Kyle Chayka about the “faux-artisanal aesthetic” that has become so prevalent in cities across the world. The Longing for Less continues his incisive writing about minimalism, focusing on four of its aspects: reduction, emptiness, silence, and shadow. While minimalism is thought of as a lifestyle (think YouTubers who flaunt their ability to own nothing), Chayka goes back to examine its philosophical and spiritual origins. He travels to Japan; dives into the work of artists like Agnes Martin and Donald Judd; visits architect Philip Johnson’s famous Glass House.

The book is thorough. I was a little bit bored. It was more art history than cultural commentary, which I was not expecting. Still, it is a fascinating examination of the look which will come to typify the first few decades of this century. I hear that maximalism is on its way back. Thank goodness.

Speaking of minimalism, we have Whereabouts, Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest book.

Twice a week, at dinnertime, I go to the pool. In that container of clear water lacking life or current I see the same people with whom, for whatever reason, I feel a connection. We see each other without ever planning to. They come at the same time, on those same days, to escape life’s troubles.

Each chapter is a vignette from a different location — the beautician, the bookstore, the narrator’s house. Nobody is named in this book. Everybody is a shifting shadow. The vignettes are short and careful. Our narrator is matter-of-fact. She spends a lot of her time by herself, only ever sliding past other people. This is a beautiful look at the fine line between being alone and loneliness.

Lahiri wrote this book in Italian, not her first language though she is now fluent, and translated into English. There are small hints that this book is set in Italy, some of the locations are the Trattoria and the Piazza, but this is otherwise a book that could be placeless. I read this book at the end of June and I’ve now forgotten most of its happenings. I do, however, remember how it felt to read it.

I’ve just received a copy of Sally Rooney’s newest book courtesy of Times Distribution. I’ll read it this week and should get back to you soon with my review.

See you soon!