Books have long been a battleground for the “culture war”. Conservatives having meltdowns over what books are taught in schools, what books are available in libraries, what books aren’t in print any more. Many of these grievances are invented. An updated curriculum, a more diverse children’s shelf at the library, or an estate deciding not to reprint outdated and racist imagery does not constitute the end of free speech.

This issue of the newsletter isn’t about any of those incidents. It’s about the publishing industry cashing in on controversy.

One of the biggest publishing houses in the world, Simon and Schuster, was recently in the news for being Post Hill Press’ distributor. Post Hill Press is an independent publisher of conservative books and had signed a deal with one of the police officers who shot the late Breonna Taylor in a raid last year. I don’t think that cops should have publishing deals to tell “their side” of the police brutality story and I’m not alone. An online petition was started to pressure Simon and Schuster to cancel their distribution deal for the book, garnering over 40,000 signatures.

The petition worked and Simon and Schuster has distanced itself from the book, titled The Fight For Truth: The Inside Story Behind the Breonna Taylor Tragedy. However, S&S is still under fire for its seven-figure book deal with former American Vice President Mike Pence. Staff members, signed writers, and other members of the literary scene have signed a petition urging S&S not to publish any books from former members of the Trump administration. As this Guardian article about the petition points out, S&S also has book deals with critics of the Trump administration, including forever Democrat Hillary Clinton.

Simon and Schuster isn’t the only large publishing house in this position. Staff at Penguin Random House, the biggest publishing house, held a town hall last year over their employer’s decision to publish a new book by controversial anti-identity politics writer Jordan Peterson. (I’m struggling to describe Peterson’s politics because I’m not sure he really knows what he stands for either.) Hachette staff staged a walk out to protest its acquisition of sexual abuser Woody Allen’s memoir. The memoir was later published under Arcade, a much smaller outfit with a staff of only 56.

I fully support collective action undertaken by the staff of publishing houses. Mike Pence’s politics repulse me and I would have a crisis of conscience if I was part of a team that was further publicising and normalising his world view. That said, at the risk of sounding defeatist, these incidents are par for the course at a large publisher. Hachette and PRH are billion dollar companies. S&S is not far behind. These are 3 of the 5 largest publishers in the world, as long as PRH doesn’t buy one of the other 4 out. (It is perilously close to owning S&S.)

It’s tempting for “book people” – readers, writers, people who take #shelfies – to think that books are inherently moral. Literate liberals love the idea that they’re superior because “conservatives don’t read”.

Conservatives do read and sometimes the books they read are by murderous police officers or Mike Pence or that racist British woman who got banned from Twitter. The amplification of “cancel culture” discourse, a belief in society’s persecution of conservatives, and publicity from conspicuous consumption guarantees that most high profile conservative authors will generate sales.

Consumers could boycott all Simon and Schuster books but they’d also end up boycotting authors they agree with and want to support. There is very little ideological purity at that level of publishing. The big conglomerates are not moral actors, they’re corporations. Publishing houses are full of passionate employees but the ones calling the shots are dyed in the wool businesspeople. And most short-sighted businesspeople only care about sales.

Publishing is predictable – readers pick up books on recommendation (the press, social media, or word of mouth) or on the reputation of the author. Big names sell well so publishers sign big names, even if they court controversy. Every now and again, there’ll be a debut writer who catapults to stardom on the back of an Oprah recommendation or a rumoured movie deal. However, the vast majority of books don’t sell more than 5,000 copies. Short of ending capitalism or, at least, passing some pretty strong anti-monopoly legislation in the book industry, I don’t think this problem is going away.

We can take defensive action against shitty books, but it’s more fun if readers rallied to promote books and writers they do like. I try to incorporate new releases, debuts, and titles from independent presses into my reading diet as much as possible. There are so many fantastic titles that slip under the radar because they don’t have big PR budgets or aren’t written by celebrities. Not only do I have a higher chance of finding something that’s genuinely surprising and novel (sorry for the pun), I’m also contributing to a more vibrant literary scene that has space for the writers who don’t grab headlines.

What I’ve read recently

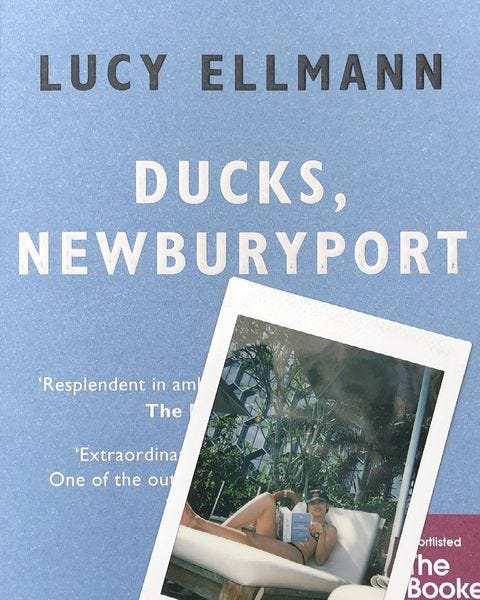

Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellman

A Booker-nominated title doesn’t really fit the bill for an unknown book BUT hear me out. Ducks, Newburyport was published by Galley Beggar Press, an independent publisher that took a chance on this monster of a book when Ellman’s usual press, Bloomsbury, wouldn’t. When people describe Ducks, they usually talk about its form rather than its plot. I have two guesses why. The first is that its form is so arresting, you can’t help but talk about it. This is how the New York Times described it:

For most of its 1,000 pages, Lucy Ellmann’s brilliantly ambitious seventh novel follows the unspooling consciousness of an Ohio housewife circa 2017, and does so almost entirely in one long, lyrical, constantly surprising sentence.

The Globe and Mail focused on its size, saying “the 1,020 page book weighs 2.7 pounds – that’s the average weight of the adult mallard that graces its cover.”

The second reason is that it’s just difficult to describe its plot. Ducks is about nothing just as much as it’s about everything. The book is the internal monologue of a suburban mother in Ohio. She starts every thought with the phrase “the fact that” and they range from rumination on global warming to what her children might enjoy for dinner. The mammoth size of this book was entirely necessary. It did take me forever (2.5 months) to read it but it was immersive. I needed the first 500 pages to familiarise myself with the narrator’s rhythm, the monotony of her daily life. The next 500 pages was just me spending time with a friend. This is a really stunning book, I’m so glad I committed to reading it. I have a lot more to say about it so email me if you want to chat! Please gaze upon my celebratory Instagram post.

Long Live The Post Horn! by Vigdis Hjorth

Long Live The Post Horn! is a novel by Norwegian writer Vigdis Hjorth, translated by Charlotte Barslund for the independent leftist press Verso Books. The book starts out like many of the books I usually gravitate towards – a disaffected young woman is bored with her life and contemplates the uselessness of it all. Ellinor works in PR. She doesn’t hate her job but it doesn’t excite her either. She has a boyfriend. He’s fine. It’s always cold in Oslo. She doesn’t really know what to say to anybody any more. This tale of ennui sets the stage perfectly for a genuinely rousing story about unions and the power of labour organising. Ellinor’s agency is tasked with the comms for a campaign to fight an EU directive that will privatise part of the Norwegian postal service. The postal service is a great metaphor for human connection and communication but this novel is also very much about the literal postal service. Long Live The Post Horn! is incredibly effective realist political fiction. I was very moved.

Happy Hour by Marlowe Granados

This debut novel is set to be published by Verso in September but it was first published in Canada by a new independent press, Flying Books.

I’ve been thinking about what constitutes “hot girl” literature ever since I gave this newsletter its joke title. (Yes, it’s a joke. Credit to my friend Natacia for the name.) Is hot girl literature what hot girls read? (Instagram girls love Sally Rooney. And Joan Didion. I’m not jazzed about her. My friend Julia once described her writing perfectly in a sentence: “Didion thinks she is the zeitgeist.”) Or is it literature about hot girl concerns? Writers like Jia Tolentino, especially her essay on optimisation, come to mind.

Happy Hour is probably the hot girl book. Best friends Isa and Gala are 21-year-old drifters spending a summer in New York City. They don’t have real jobs or responsibilities beyond themselves. They get free taxis and party entry based on their sheer charm. Nothing really happens in this book. They go to parties, they meet social climbers and loser men, they drink, they hustle, they wear beautiful things. We read Isa’s diary as she chronicles how the girls meander through the months. They are magnetic and mysterious. They are brats. What this book captures perfectly is how nobody around them can decide if they should be treated like dolls or adults. There are doors that open, and doors that close, precisely because being an attractive young woman is a precarious position in society.

I’m lying, I haven’t read this yet! I really loved Lau’s first book, Pink Mountain on Locust Island, so I have ordered Gunk Baby despite not knowing what it’s about. I’ve included this because preorders help publishers anticipate interest which is really great for newer authors.

Once again, I have written too much

I’m always interested in independent presses and titles so feel free to send recommendations my way. See you next time!!